Why Your Period App Could Use a Feminist Update

Tracking your cycle, health, and well-being is easier than ever with period apps. But what is happening with the data and what role does app design play in this? The influence of period apps and their often unreliable predictions and data sharing with third parties raises concerns for the privacy and safety of users. Flavia Saxler was the digital product owner at theblood and lead product research gathering insights on menstruation technologies. She argues that although period apps offer many opportunities for people in terms of taking control of their bodies, fertility, and contraception, there are pitfalls with their privacy practices, algorithmic predictions, data transparency, and hetereonormative design. Ultimately, she advocates for a feminist approach to the design and deployment of period-tracking technologies to engage with everything that these digital products can do for the safety of the user, and in the end, for shaping a more equitable future.

The Good and the Not-So-Good of Period Apps

Period apps have become a go-to tool for keeping tabs on the menstrual cycle and reproductive health. They are handy for understanding your body, predicting your period, and even managing conditions like endometriosis. But there is a catch. Some of these apps are not as private, reliable, and empowering as they seem.

Period apps have become increasingly popular in the last decade, providing a convenient way for individuals to digitally monitor their menstrual cycles and track various aspects of their reproductive health [1]. While these technologies offer many benefits, including autonomy over menstruation, their design, development, and deployment also raise important ethical questions about data privacy and empowerment. In academic discourse, period apps for a long time have been criticized for their design and surveillant logic [2]. Also in public discourse, writers investigate how period apps are feeding into ‘menstrual surveillance’ by sharing data with employers and health insurers [3].

After Roe v. Wade was overturned, ending the right to abortion, experts warned users of period apps of their privacy settings and data sharing practices and encouraged users to evaluate if it is worth the risk [4]. Sociologist and Director of the Minderoo Centre for Technology and Democracy, University of Cambridge tweets that users should “delete every digital trace of any menstrual tracking” [5]. The Mozilla Foundation found that almost all period apps are sharing data with third parties [6]. This phenomenon became increasingly dangerous in the post-Roe v. Wade era in the United States as these apps could potentially share data with law enforcement. Users should be aware of this when using them to avoid unwanted pregnancies and logging sensitive information into the app. Even though in many other countries there is still a right to abortion it shows what could happen with data and their impact on people’s lives if laws are overturned.

Not only the data-sharing practices of period apps are under criticism, but also their design and features, which reflect certain social norms on menstruation and gender [7]. The design of technology is never neutral, but rather reflects the values of the developers and, hence is a ‘moral act’, that can be good or evil [8]. Especially, femtech technologies, such as period apps, promise users empowerment and want to ‘do good’, yet research shows that such apps often build upon normative femininity and heterosexist norms of female sexuality further contributing to issues they want to solve [9].

Yet, period apps are not all bad, on the contrary, they can be a powerful force for good, and thus need critical investigation to develop even better and more equitable digital menstruation technologies for the future.

Let's dive deeper into why these apps need a feminist makeover to ensure your privacy, inclusivity, and empowerment.

Privacy: Intimate Data, Algorithmic Predictions and Transparency

Are you aware that period tracking apps are accumulating a treasure trove of personal data, raising profound questions about privacy and potential legal implications?

Period apps collect various, very private, information about the body and mind of the user: the start and end dates of periods, weight, height, symptoms, moods, and sexual activity. The information collected is often very intimate, such as sexual preferences, contraceptive use, medication, mental health, basal body temperature, cervical mucus consistency, ovulation test results, and journal notes. As the image below shows, the app Flo gives detailed options to let the user tell if for instance they had practiced anal sex or had an orgasm. This sensitive health data is said to be used to predict future periods and provide health insights and personalized recommendations. However, it remains unclear how the app uses those data points and what role they play in predictions and personalized recommendations. The user can log in sensitive information and what they receive in return, on the free version, is relatively simple and can also easily be calculated using a notebook calendar and adding the approximate cycle length days. This calendar-based method was invented in the 1930s and most apps still function based on it [10].

Many apps market themselves by using advanced technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI) and/or machine learning (ML), however, there is a lack of transparency on how data exactly is used for what kind of predictions. Apart from untransparent prediction algorithms, the apps are often also ineffective in their predictions of future menstrual cycles as those are prone to individual deviations (i.e., stress), as well as apps often fail to consider life stages that women experience as adolescence and menopause [11].

Yet, opacity is not confined to prediction algorithms alone; it extends to the privacy practices of these apps. Some apps begin collecting user information before consent to privacy policies is granted or bury such policies within lengthy terms and conditions. In some cases, app functionality is contingent upon accepting these policies and specific data practices. Disabling data sharing options can also be a labyrinthine task in certain user interfaces. The lack of clarity and accessibility in privacy policies undermines the autonomy of users over their data. Additionally, the data gathered may potentially be exploited by advertisers or shared with third parties [12].

A recent report from the IoT Transparency project underscores the growing importance of transparency in safeguarding user privacy and data security [13]. The existence of regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) does not guarantee full compliance by companies, especially concerning practices like sharing data logs with users or sending data to undisclosed locations. The report emphasizes the urgent need for clear and easily accessible information regarding data collection, storage, and sharing practices, extending not only to apps but also to Internet of Things (IoT) devices, such as wearables [13]. Privacy International tested five period apps for their data compliance: out of the five apps they have analyzed only two apps responded, one app did not give the data, one never responded, and one is refusing to publish data [27]. This result shows the same findings as the IoT transparency report, not all companies are compliant with GDPR when it comes to sending the users their data.

In light of these concerns, users must remain vigilant regarding the data-sharing practices of these apps and carefully deliberate over their privacy when engaging with them.

Empowerment: Gendered Design and Features

Ever noticed that many period apps are filled with flowery and pink designs? That is not a coincidence but shows how biases can be encoded into the app's interface that might reinforce outdated stereotypes.

But not only opaque data sharing practices can undermine users’ autonomy, and thus empowerment, but also heteronormative design choices that amplify notions of ‘traditional’ femininity can reinforce gendered stereotypes. Researchers critically analyze how design and app features are shaped by ideologies and recode gendered biases, norms, and assumptions. The interfaces of apps are not neutral intermediaries but represent certain social norms and logic of the developers [8]. This question, of whether technologies have politics, long has been discussed in academic discourse [16]. For example, the design of one at-home test symbolizes ovulation with a happy smiley relating a positive emotion to fertility, and reshapes the norm of a feminine wish to be a mother. Technologies are not neutral but depend on the developers’ input for the design of the interface and development of the underlying algorithm [15].

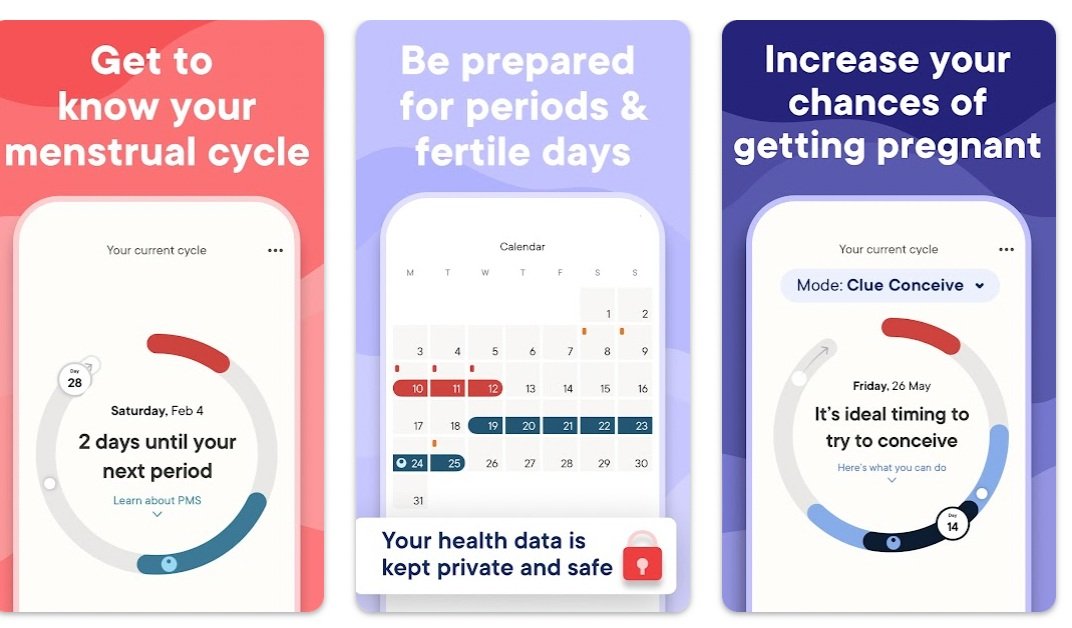

Images: Screenshots from AppStore Period Apps, Screenshot from ‘Period Diary’ App, Stockphoto with search term ‘period app’.

Many apps use gendered design which comes with flowers, feathers, and pink [16]. These gender-normative designs in products and services can recode sexism and need to be critically assessed. For example, some period apps are designed with icons such as a flower can reinforce notions of stylization of menstruation as also used in advertisements, where the blue liquid in the pad and tampon is used to visualize menstrual blood [17]. Period apps are an interesting counterexample to other fitness, health, and well-being apps, which often are in blue, green, and yellow designs, and are marketed to ‘all’ users and not only menstruating people.

Moreover, the focus of features for many apps is around fertility: tracking ovulation and the end and start date of periods. However, there is way more to the menstruating body than tracking fertility, especially in times when birth rates are dropping drastically [18]. Many are less interested in becoming pregnant and even though this is an indication of an exercise of control over their body it also shows a social shift in people’s priorities. Some scholars argue that period apps reinforce the alienation of the body by not trusting bodily intuition but digital tools and further amplify the concealment of menstruation by ‘glamorizing’ it [19].

Courtesy of Clue.

The period app Clue is a good example of a more gender-neutral design and options for the user to change the aim of the app beyond fertility and conceiving. Furthermore, Clue acts upon stricter GDPR privacy laws, compared to US-based companies, and the Mozilla Foundation rates their privacy as “ok”, but there is also room for improvement [20].

Technologies should function as advocates of social processes and understand their power to encode social biases and perpetuate historic inequalities. For instance, the option to share menstruation data with the partner can be linked to past practices where the partner tracked the period of his wife with a calendar to plan pregnancies. The digital tracking of menstruation can also be misused, as some years ago, there were apps specifically for men to track when their co-workers were on their period and/or PMSing to avoid them [21]. Hence, just sharing data is not enough and can also be misused for intimate surveillance [22]. A more equitable approach would be for instance to share the costs of the app or fertility service. Digital products can be improved when utilizing a critical lens to design solutions that empower the user.

How Data Feminism Can Help

When it comes to period apps, data feminism challenges us to think about whose experiences are being represented and whether we have control over our data. It is not about merely criticizing technologies and data but thinking about alternatives and ways to improve to design better products that people feel safe with.

Data feminism is a framework developed by the two researchers D’Ignazio and Klein, that advocate for the use of data to promote equality and highlight asymmetric power relations and hidden inequalities [23]. An example is the autocomplete feature in Google searches that reinforces gender stereotypes and bias. Safiya Noble shows in her work on Algorithms of Oppression how Autocomplete suggestions can be offensive [24] . For instance, the Autocomplete feature when one types in ‘women should’ or ‘women need’ that shows ‘women should stay at home’ or ‘women need to be put in their place’ perpetuates harmful gender norms.

This Autocomplete feature also shows similar stereotypes in other search engines i.e., Adobe Stock Photo. While typing in ‘women’ the suggestions are mainly focused on looks like ‘women beauty’, ‘women fashion’, and ‘beautiful women’ and sexualizing them as ‘women sexy’ and ‘naked women’. It depends not only on the data input - what people are searching for the most - but also depends on the underlying algorithm. As Google’s official statement highlights: “Autocomplete is a time-saving but complex feature. It doesn’t simply display the most common queries on a given topic” but “also predict[s] individual words and phrases that are based on both real searches as well as word patterns found across the web” [25].

So, what does data feminism have to do with period apps?

Data feminism encourages a critical examination of data collection, analysis, and representation practices and the biases that may be embedded within them. In the case of period apps, it offers a way to critically examine the assumptions and biases that may be present in data collection and visualization. For example, many period apps are designed with cisgender, heterosexual women in mind, and may not account for the experiences of transgender or non-binary individuals [7]. Data feminism encourages us to ask questions like:

Whose bodies and experiences are being represented in these apps? Whose needs are being prioritized? And how can we ensure that these technologies are inclusive and empowering for everyone?

Principles of Data Feminism applied to Period Apps.

As outlined before, the data collected through period apps has important implications for the user. For example, they can help users identify patterns in their menstrual cycle and symptoms, which can be useful for managing conditions like endometriosis. However, the data collected by these apps can also be used to reinforce harmful gender stereotypes or perpetuate gender-based discrimination through their design and deployment. Also extracting information from users, without giving them a lot in return can have harmful impacts [26]. By applying the principles of data feminism to the design and deployment of period apps, those can critically assess power and gendered stereotypes.

The Future of Menstruation is Now

Period apps have immense potential, but their path ahead needs a course correction. They can inadvertently reinforce biases, exclude diverse experiences, and hoard intimate data without offering users much in return. It is time for a feminist overhaul to put users back in control.

Period apps can incorporate privacy-preserving features, such as in-app features to turn tracking off and not share data. Transparent, which means accessible, understandable, and easy-to-find privacy policies can further help to empower users and their control over their data. Apps can use the data minimization principle, where less is more, and only relevant and for the user benefitting data points are tracked. A good practice example is the straightforward privacy policies of the app Stradust.

Period apps can be designed to be more inclusive of diverse gender identities and experiences. This for instance can include providing options for non-binary and transgender users to track their menstrual cycles, giving the user the option to not focus or hide features considering fertility, and offering features that cater to individuals with irregular periods or menopause. Additionally, apps can use gender-neutral language and more neutral designs to avoid perpetuating gender stereotypes and stigma. A good practice example of a more gender-inclusive design is the app Clue.

Period apps can be designed to empower users with information and education about reproductive health beyond fertility. This can include providing resources and information about mental and physical well-being, hormones, nutrition, and sexual health. Apps can move beyond conventional interfaces that primarily highlight ovulation and period duration and create user-friendly designs that prioritize a comprehensive understanding of menstrual well-being beyond pregnancy. A good practice example is the Femble which describes itself as a ‘hormonal cycle companion app’.

The path forward transforms menstrual data into a force for good, revolutionizing how we navigate this digital landscape.

It is crucial to think critically about how self-tracking data is used beyond individual contexts, considering the broader societal and ethical implications. The vast collection of data without transparent mechanisms of what, how, and why data is collected and where it is sent can have an unprecedented impact on reproductive health in the future, which shockingly shows in the US.

More period apps incorporate user feedback, respond to backlashes on their privacy practices, and change user interfaces. A good practice example for feminist data activism and intervention is the non-commercial open-source period app Drip which stores data locally on one’s phone and shows users the workings of the underlying algorithm. The app aims to make period tracking more transparent and secure. It is based upon feminist principles of “your data, your choice” and does not aim to be “another cute, pink app” but aims for gender inclusivity. It is unclear how successful this app might be, but the principles it is built upon pave the way to valuing user autonomy, data transparency, and designing for a more equitable future. The app already has been used by academic discourse as an example of a period app that truly empowers the user by putting their privacy and safety first [10].

In the end, being critical of those processes is a needed lens to design and deploy safer products that respect individual rights and promote ethical technological innovation. By integrating data feminism principles, we can shape a future where period apps are empowering, inclusive, and ethically responsible, revolutionizing the way we approach menstrual data collection, storage, analysis, and visualization.

This article represents the views of the author.

Flavia Saxler is a PhD student at the University of Cambridge, a member of the Cambridge Reproduction network, and a student fellow at the Leverhulme Institute for the Future of Intelligence, University of Cambridge. She researches the societal and ethical implications of data-powered safety technologies on women’s safety, well-being, and privacy in the United Kingdom. Furthermore, she works on a collaborative project with the Complaint and Accountable Systems Group at the Computer Lab, Cambridge on data safety and privacy of data-enabled fertility wearables. Her research strives to uncover the balance between technological advancement and human vulnerability, shedding light on privacy risks and algorithmic transparency in a post-Roe v. Wade landscape.

Flavia loves tech products and investigates their safety for users. She analyzes tech features and envisions innovative possibilities with AI and data along the lines of data privacy. She finds her tech-savvy heart dancing to the beats of pop music playlists on Spotify and navigating exciting journeys to the best pasta places in town with Google Maps.

References

[1] Novotny, Maria, and Les Hutchinson. ‘Data Our Bodies Tell: Towards Critical Feminist Action in Fertility and Period Tracking Applications’. Technical Communication Quarterly 28, no. 4 (2 October 2019): 332–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2019.1607907.

[2] Ford, Andrea, Giulia de Togni, and Livia Miller. ‘Hormonal Health: Period Tracking Apps, Wellness, and Self-Management in the Era of Surveillance Capitalism’. Engaging Science, Technology, and Society 7, no. 1 (5 October 2021): 48–66. https://doi.org/10.17351/ests2021.655.

[3] Mahdawi, Arwa. ‘There’s a Dark Side to Women’s Health Apps: “Menstrual Surveillance”’. The Guardian, 13 April 2019, sec. Opinion. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/apr/13/theres-a-dark-side-to-womens-health-apps-menstrual-surveillance.

[4] Elliott, Vittoria. ‘Period and Fertility Apps Can Be Weaponized in a Post-Roe World’. Wired, 7 June 2022. https://www.wired.com/story/fertility-data-weaponized/.

[5] Hill, Kashmir. ‘Deleting Your Period Tracker Won’t Protect You’. The New York Times, 30 June 2022, sec. Technology. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/30/technology/period-tracker-privacy-abortion.html.

[6] Mozilla Foundation. ‘In Post Roe v. Wade Era, Mozilla Labels 18 of 25 Popular Period and Pregnancy Tracking Tech With *Privacy Not Included Warning’, 17 August 2022. https://foundation.mozilla.org/en/blog/in-post-roe-v-wade-era-mozilla-labels-18-of-25-popular-period-and-pregnancy-tracking-tech-with-privacy-not-included-warning/.

[7] Epstein, Daniel A., Nicole B. Lee, Jennifer H. Kang, Elena Agapie, Jessica Schroeder, Laura R. Pina, James Fogarty, Julie A. Kientz, and Sean A. Munson. ‘Examining Menstrual Tracking to Inform the Design of Personal Informatics Tools’. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems . CHI Conference 2017 (2 May 2017): 6876–88. https://doi.org/10.1145/3025453.3025635.

[8] Floridi, Luciano. ‘On Good and Evil, the Mistaken Idea That Technology Is Ever Neutral, and the Importance of the Double-Charge Thesis’. SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY, 25 August 2023. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=4551487.

[9] Hendl, Tereza, and Bianca Jansky. ‘Tales of Self-Empowerment through Digital Health Technologies: A Closer Look at “Femtech”’. Review of Social Economy 80, no. 1 (2 January 2022): 29–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346764.2021.2018027.

[10]Amelang, Katrin. ‘(Not) Safe to Use: Insecurities in Everyday Data Practices with Period-Tracking Apps’. In New Perspectives in Critical Data Studies: The Ambivalences of Data Power, edited by Andreas Hepp, Juliane Jarke, and Leif Kramp, 297–321. Transforming Communications – Studies in Cross-Media Research. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96180-0_13.

[11] Worsfold, Lauren, Lorrae Marriott, Sarah Johnson, and Joyce C Harper. ‘Period Tracker Applications: What Menstrual Cycle Information Are They Giving Women?’ Women’s Health 17 (1 January 2021): 17455065211049904. https://doi.org/10.1177/17455065211049905.

[12] European Digital Rights (EDRi). ‘Period Tracker Apps – Where Does Your Data End Up?’ Accessed 31 August 2023. https://edri.org/our-work/period-tracker-apps-where-does-your-data-end-up/.

[13] Anna Ida Hudig, Chris Norval, and Jatinder Singh. ‘Transparency in the Consumer Internet of Things’. Transparency in the consumer Internet of Things. Accessed 6 July 2023. https://listenforchange5.wordpress.com/.

[14] Winner, Langdon. ‘Do Artifacts Have Politics?’ In The Whale and the Reactor: A Search for Limits in an Age of High Technology, 19–39. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1986.

[15] Benjamin, Ruha. Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. 1. edition. Medford, MA: Polity, 2019.

[16] Levy, Johanna. ‘“It’s Your Period and Therefore It Has to Be Pink and You Are a Girl”: Users’ Experiences of (de-)Gendered Menstrual App Design’. In Proceedings of the 4th Conference on Gender & IT, 63–65. GenderIT ’18. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1145/3196839.3196850.

[17] Przybylo, Ela, and Breanne Fahs. ‘Empowered Bleeders and Cranky Menstruators: Menstrual Positivity and the “Liberated” Era of New Menstrual Product Advertisements’. In The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies, edited by Chris Bobel, Inga T. Winkler, Breanne Fahs, Katie Ann Hasson, Elizabeth Arveda Kissling, and Tomi-Ann Roberts, 375–94. Singapore: Springer, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-0614-7_30.

[18] United Nations Population Fund. ‘The Problem with “Too Few”’. Accessed 6 July 2023. https://www.unfpa.org/swp2023/too-few.

[19] Kressbach, Mikki. ‘Period Hacks: Menstruating in the Big Data Paradigm’. Television & New Media 22, no. 3 (1 March 2021): 241–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476419886389.

[20] Mozilla Foundation. ‘*Privacy Not Included Review: Clue Period & Cycle Tracker’. Accessed 5 September 2023. https://foundation.mozilla.org/en/privacynotincluded/clue-period-cycle-tracker/.

[21] Elite Daily. ‘Men Are Tracking Co-Workers’ Periods To Avoid Interacting With “Moody” Women’, 6 September 2016. https://www.elitedaily.com/women/period-apps-men-track-moodiness/1601587.

[22] Levy, Karen E. C. ‘Intimate Surveillance’. Idaho Law Review 51, no. 3 (2015 2014): 679–94.

[23] D’Ignazio, Catherine, and Lauren F. Klein. Data Feminism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2020.

[24] Noble, Safiya Umoja. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. NYU Press, 2018.

[25] Graham, Rosie. ‘The Ethical Dimensions of Google Autocomplete’. Big Data & Society 10, no. 1 (1 January 2023): 20539517231156520. https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517231156518.

[26] Worsfold, Lauren, Lorrae Marriott, Sarah Johnson, and Joyce C Harper. ‘Period Tracker Applications: What Menstrual Cycle Information Are They Giving Women?’ Women’s Health 17 (1 January 2021): 17455065211049904. https://doi.org/10.1177/17455065211049905.

[27] ‘We Asked Five Menstruation Apps for Our Data and Here Is What We Found... | Privacy International’. Accessed 1 September 2023. http://privacyinternational.org/long-read/4316/we-asked-five-menstruation-apps-our-data-and-here-what-we-found.